A highly political, highly politicised topic. The most simplistic picture: the prosperous get richer at the expense of the poor. The most simplistic solution: higher minimum wages and/or taking more (tax) money from the prosperous will make the world more equitable.

In the present political environment it is particularly important to look at the facts very carefully, and to try to understand some of the drivers of the change in relative household incomes, also understand the differences between advanced and emerging economies. Understanding these trends and drivers is also and in particular important for a food company, because this is about our consumers.

And it is important to keep the right perspective on the real problem: for those with very low incomes it is not the Gini-index that matters, but how to make sure there is a way to improve (or at least not deteriorate) their situation.

A few points on developments in advanced economies:

Between 1915 and 1980, income distribution followed the Kuznets curve after the turning point (separate paper enclosed). Developments of the last 35 years must be seen in a longer-term context (chart enclosed): Sweden from 25% for the top percentile before WWI for to less than 5% in 1980 (and similar developments for many other OECD countries). To talk about “record inequality between rich and poor”, as OECD and others do, is therefore a slight exaggeration.

What happened with real household income in OECD27, mid 1980s to late 2000s? Income differentials have been increasing again – but to levels still far below those before WWI. The OECD report “Divided we stand” (Paris 2011) provides the data: for the top decile plus 1.9% per annum, for the bottom decile plus 1.3% per annum. Over these 30 years, the 1.3% per annum growth for the bottom decile adds up to an improvement of close to 50% — as mentioned in real terms. The low income groups are not getting poorer.

Some of the drivers of these differences in growth rates after 1980:

In the last two decades before the turning point, there was no longer mainly market led re-balancing of incomes, but compression of wage and income differentials driven by the heavy hand of the state (e.g., scala mobile in Italy), leading straight into the Eurosclerosis of the late 70s and early 80s (little incentive to work hard, to invest in education).

After 1980, adding a few hundred million Chinese and Indians to the world’s productive labour force slowed the rise in income for workers all over the developed world. But structural change in industry corrected a lot of this; where this structural change was blocked by government interventions, the low income groups had to pay. There is one more aspect to this: imports from newly industrialised countries changed also the relative prices of goods; prices of goods that the poorer people tend to consume have fallen sharply relative to the prices of goods that rich people consume. Taking this into consideration, US inequality, for instance, grew two-thirds less than standard measures would suggest.[1]

Today, there seems to be a greater importance of good education for income (particularly two-income households, he and she with high qualifications). Often high cost of this education, e.g. in USA, that needs to be recovered (net lifetime income would for the US provide a different picture)[2]. And one may also add that increasing wage differentials work as an important incentive for people to actually invest in education (ultimately adding prosperity for all).

On the high income side: the long-term chart from Roine and Waldenstrom makes an interesting distinction for Sweden after 1980: when including capital gains, increase in the income share of the top percentile to 8-10%; excluding capital gains: share more or less flat at 5% (chart enclosed).

Some people actually left behind, e.g., today, the worst paid people in Switzerland, for instance, are chamber maids in hotels, a sector where little structural change, little improvement due to better education was possible. And there are societal factors we see in Switzerland (but also in other OECD countries): the highest risk to fall back in household incomes is for divorced couples with children, the one who raises the children alone and the other who has to pay alimony – for the background: divorce rate in Switzerland increased from 25% in 1980 to more than 50% today[3]; similar data again for other OECD countries.

Outlook advanced economies (OECD):

For quite some years to come little optimism for further capital gains of the top percentile. But if Europe s still able to generate some growth and remain competitive, if structural adjustment can continue, there is no reason to believe that there cannot be at least some modest further growth for those in the productive process – maybe below the 1.3% per annum for the lowest decile as over the last 30 years. Most of the recent announcements for tax hikes, however, imperil this moderately positive outlook.

There are, however two further major risks:

- High youth unemployment today, more than 50% in some OECD countries. If these youngsters stay out of work for several years they will never again enter a qualified job. Youth unemployment across Europe is directly related to labour market inflexibility, including minimum wages. Rigid labour markets hurt the most vulnerable

- Uncovered age-related entitlements: Highly indebted and possibly even bankrupt states will have more and more difficulties to deliver on all of their promises. With demographic change age-related payments will rapidly increase: according to a study by the Bank for International Settlement, the central bank of central banks, these age related payments (pensions, elderly and health care) risk adding to public debt in an order of magnitude between 60 and 140 percentage points of GDP by 2040 – for countries such as France, Germany, UK, USA and the Netherlands. Needless to say that these huge contingent liabilities appear nowhere in the books.

Emerging economies (see also separate post on the Kuznets curve):

India (PPP USD 5,800 p.c.) and China (PPP USD 12,900 p.c.) are still left of the Kuznets turning point, but getting closer relatively fast. According to IMF GDP forecasts, China may pass the point already towards the beginning of the next decade.

Outlook: The main risk today and in the years to come for those who stay poor: prices of basic (staple) food, i.e., simple forms of calories and proteins that can be the equivalent of up to 50% of household budgets of people in poor countries. With the food price crises 2008 and 2010, around 200 million people again fell below the poverty line – actually below an income where they go hungry to bed.

Conclusion: (quoting a CATO paper from 2009):

“(Debate on) income inequality is a dangerous distraction from the real problems (that need to be addressed): poverty, lack of economic opportunity, and systemic injustice.” Inclusive growth is about opportunity, about improvement, not about status-quo measurement of Gini coefficients. Inclusion is about getting a chance, and about the willingness to contribute to the common good.

And a final quote, from Abraham Lincoln: “You cannot strengthen the weak by weakening the strong. You cannot bring about prosperity by discouraging thrift. You cannot help the wage-earner by pulling down the wage-payer.”

[1] John Broda and Christian Romalis, Inequality and prices: Does China benefit the poor in America?, University of Chicago Working Paper, March 2008.

[2] According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, total student debt (which includes private loans and federal loans) climbed to more than $1 trillion.

[3] http://www.hoepflinger.com/fhtop/Wandel-der-Familien.pdf

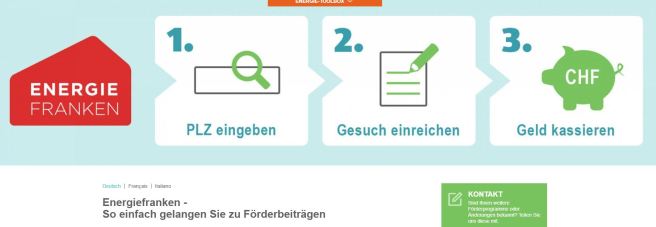

When you do a web search on energy subsidies in Switzerland, you won’t find some broader overview summarizing the total cost, even less a cost-benefit analysis, but wonderfully designed webpages on ‘how to get more of them’, with a broad diversity of offers by different levels and sections of government, with layouts that look like a combination of Amazon and offers of wellness resorts offering eternal happiness.

When you do a web search on energy subsidies in Switzerland, you won’t find some broader overview summarizing the total cost, even less a cost-benefit analysis, but wonderfully designed webpages on ‘how to get more of them’, with a broad diversity of offers by different levels and sections of government, with layouts that look like a combination of Amazon and offers of wellness resorts offering eternal happiness.